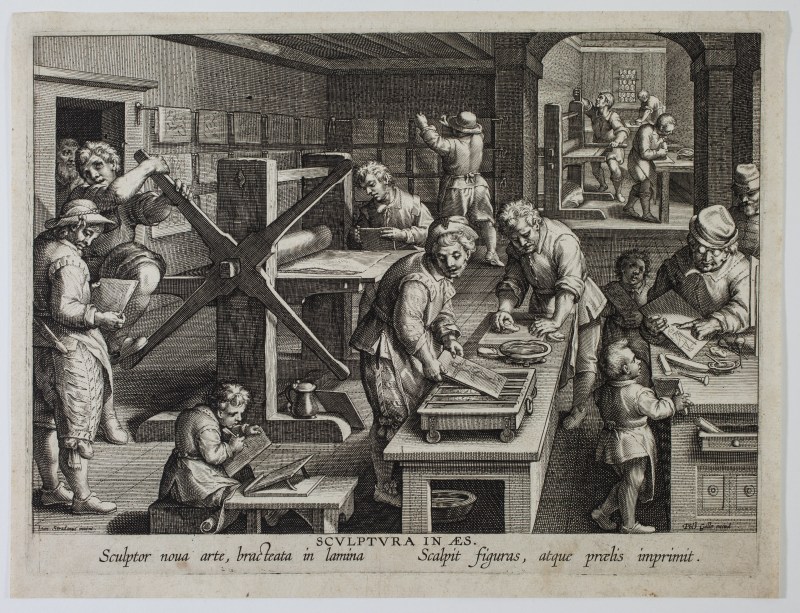

After Johannes STRADANUS: Sculptura in æs - ca. 1591

SOLD

[The Invention of Copper Engraving]

Engraving, 203 x 274 mm. New Hollstein (Johannes Stradanus) 341, 1st state (of 4).

Impression of the 1st state (of 4), before the number 19 in the lower left margin, with Philips Galle’s address, before Johannes Galle’s address. Impressions of the 1st state are very rare.

Superb impression printed on laid watermarked paper (watermark: gothic P). In excellent condition. Small margins around the platemark (sheet: 218 x 287 mm).

Sculptura in æs is part of a series of twenty engravings; the first plate in the series has the title Nova Reperta. This series was engraved by several artists after Johannes Stradanus; not all of them have been identified. Some plates are signed by Theodoor Galle (plate number 1) and Jan II Collaert (plates 15, 17 and 18). Four other plates have also been attributed to the latter: the plates with numbers 2, 12 and 16, as well as the title plate (see New Hollstein, The Collaert Dynasty, nos. 1205-1211). The series was first published around 1591 by Philippe Galle in Antwerp and was then successively republished by Karel de Mallery (after 1612), Theodoor Galle (before 1636) and Johannes Galle (before 1677).

The Nova Reperta series illustrates several noteworthy discoveries and inventions in late 16th century Europe: ranging from the exploration of the Americas to the cultivation of sugarcane, including the invention of the compass or the development of gunpowder. Impressio librorum and Sculptura in æs represent a typographical printer’s shop for the former, and a workshop for intaglio printmaking for the latter.

Sculptura in aes represents the different operations carried out in a printing workshop. In the foreground, an engraver is teaching the technique to two children, while a third child, seated at a small desk on the left, is busy copying a drawing. The other workers are busy with the different tasks, each one corresponding to one of the successive stages of printing a copper plate: preparation of ink and sheets, varnishing, heating and wiping the plate, inking, passing under the press, checking the finished prints, hanging up the sheets to dry. The composition representing the different phases of the printing process both in space and in time creates a movement that evokes not only the hustle and bustle of a workshop but the dynamism of a new industry born of a « technical invention", which is the theme of the Nova Reperta series.

Sculptura in æs puts the emphasis less on the invention of copperplate engraving, and more on the invention of the roller press, which allowed intaglio to soar as an art. Ad Stijnman, who undertook an exhaustive study of the history of the development of manual intaglio printmaking processes in his book Engraving and Etching 1400-2000, notes that, when copperplate engraving appeared in Europe around 1430, it wasn’t done with a press but by hand, by rubbing the back of the paper laid against the copperplate. This would result in very weak impressions of unequal quality. The use of roller presses was probably inspired by textile printing presses and started around 1460-1465. According to Jacques Bocquentin, as quoted by Ad Stijnman, the first roller press appeared in 1460-1465 in the Upper Rhine region, possibly in the workshop of the Master E.S. (Stijnman p. 39). The first known depiction of an engraver’s workshop is a small woodcut, attributed to Arnold Nicolai, that was introduced in the 2nd edition of Emblemata, et aliquot nummi antiqui operis by Johannes Sambucus, published by Plantin in 1564 in Antwerp. The scene is rather simplistic and features only one character. Sculptura in æs is the first detailed and realistic depiction of an engraving workshop, where the division of tasks evokes the level of sophistication of the process as well as the distribution of a high number of impressions.

Madeleine C. Viljoen sees this print as "both a meta -engraving, illustrating how engravings are made, and the first image to publicize the mise-en-scène of early modern engraving. " (p. 61) She considers that there is a "mise-en-scène" in the fact that « the scene of calm that Stradanus 's Sculptura in æs presents belies the realities of early modern printing shops, which scholars have shown were noisy, mucky, and rowdy" (p-63-64). According to her, this idealised vision corresponds to a new expression of the union of labor and diligentia. "The union of diligence and labor is a common conceit in mid-sixteenth-century Flemish and Netherlandish prints." (p. 70) The letter of Hendrick Goltzius’s Labor et Diligentia (1582) reads : “When labor and diligence are not spared, the arts will bring forth diverse inventions” (translated from Dutch by Madeleine C. Viljoen, p. 70).

References: Ad Stijnman , “Stradanus’s Print Shop”, Print Quarterly, vol. XXVII (2010) no. 1, pp. 11-29; Ad Stijnman: Engraving and Etching 1400-2000, A History of the Development of Manual Intaglio Printmaking Processes, 2012; Madeleine C. Viljoen: "Diligent labor in Stradanus's Engraving Shop" in Renaissance Invention: Stradanus's Nova Reperta, pp. 61-73, 2020.