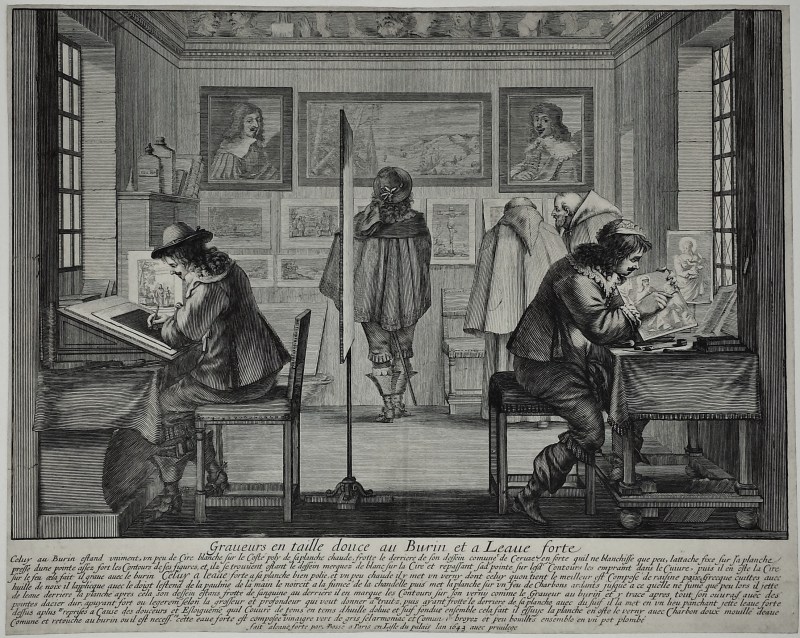

Abraham BOSSE: Graveurs en taille douce au Burin et à l’Eau-forte - 1643

SOLD

[The Engraver and the Etcher]

Etching with burin, 261 x 324 mm (sheet). Blum 356, Préaud 203, Lothe 255.

Very fine impression of the only state, printed on laid paper with watermark (Arms of France: three fleur-de-lys inside a French crowned coat-of-arms).

Impression trimmed 1 to 2 mm outside the borderline. Very slight central vertical drying crease, two slight diagonal creases. Minimal rubbing in the bottom right corner. Tiny remains of paper tapes on back in the corners. Generally in very good condition.

In 1643, Abraham Bosse wrote his seminal work, Traité des manières de graver en taille-douce sur l’airain par le moyen des eaux-fortes et des vernis durs et mols. Ensemble de la façon d’en imprimer les planches et d’en construire les presses [Treatise on the art of engraving and etching on bronze, by means of acid and soft and hard ground. Together with the ways of obtaining impressions of those plates and of building presses], for which he obtained a privilege in 1642, and which he published in Paris in 1645.

This was the first ever technical textbook on engraving. It was very successful, and was translated and widely distributed in the following years in Germany, the Netherlands and in England; it was reprinted several times, with additions by Sébastien Leclerc and then Charles-Nicolas Cochin in the XVIIIth century.

The plate representing the Graveurs en taille douce au Burin et à Leaue forte [The Engraver and the Etcher], shows the same educational concern as the plate “showing how to print etchings” (qui montre comme on imprime les planches de taille douce), etched by Abraham Bosse the previous year. The workshop and the work of the engraver and the etcher are represented in exacting detail; the same level of care went into an exceptionally long and detailed caption. Maxime Préaud notes that the text goes beyond a simple description of the picture and is a forerunner of the future Treatise. We translate here his modernised version of the caption:

The engraver [on the right] spreads an even layer of white wax on the polished side of his hot plate; he rubs the back of his drawing, usually with white lead, so that it will only whiten a little, attaches it to his plate, and then, with the sharp tip of his tool, he follows the outlines of his subject, and those are marked in white on the wax once the drawing is removed; pressing again with the tip and following those same outlines, he scratches them into the copperplate; he then removes the wax, melting it near the fire; once this is done, he engraves the picture with the burin. The etcher [on the left] has his plate well polished and slightly hot; he applies a ground, of which the best, they say, is made of resin and Greek pitch, cooked with walnut oil; he applies it with his finger, spreads it with the palm of his hand, blackens it with soot from a candle, then places the plate on a fire of hot coals until it is only smoking a little; then he splashes the back of the plate with water [to cool it]. After that, his drawing being rubbed with sanguine on the back, he marks the outline on the ground as did the engraver, and then traces his whole work with hard steel tips, pressing hard or lightly according to the thickness and depth he desires to give his strokes, then, having rubbed the back of his plate with tallow, he places it on a leaning surface [like an easel for example], splashes it with acid several times, because of the light tones and distances, which he time and time again covers with olive oil melted together with tallow. Once this has been done, he wipes the plate, removes the ground with soft coal humidified with common water, and where necessary, touches up the design with a burin. The acid is made of vinegar, verdigris, ammonium chloride and common salt, ground and boiled together a little in a leaden pot.

For his print, Abraham Bosse chose etching, a technique which he constantly refined in order to get strokes as neat and clean as those made with a burin. He succeeded perfectly in this case. As noted by Maxime Préaud, the etcher “in a quest for accuracy, went as far as placing a few burin strokes next to the tip of the tool” held by the engraver, but the rest of the plate is entirely done in etching.

Etching is the main subject matter of the Traité des manières de graver en taille douce; in the Treatise, Abraham Bosse only devoted two chapters to the technique of engraving. The book contains sixteen illustrations, summarily etched. The plate representing the Printmakers, on the other hand, is similar in its dimensions and its composition to the large genre scenes that made the artist famous in his lifetime. The composition of the Printmakers, as in the plates for the series of the Five Senses or the Four Ages of Man, reminds us of a stage, with the printmakers at the front, while the background is marked by the wall of the workshop, on which are displayed modern and religious prints, which a gentleman and two Capuchin monks are perusing.

Neither a simple genre scene, nor purely an illustration, Printmakers is difficult to categorise. However, along with The Printers, it represents the best example of Abraham Bosse's art, and of his major contribution to the evolution of the technique of etching in the XVIIth century.

References: Maxime Préaud, Sophie Join-Lambert (dir.), Abraham Bosse, savant graveur, Paris, 2004. José Lothe, L’œuvre gravé d’Abraham Bosse, Paris, 2008.